The "Aroostook Expedition," at the "Theatre of Troubles," [1]

And, the Midnight Ride of Hastings Strickland

By Dena L. Winslow, Ph.D.

Hastings Strickland, the Sheriff of Penobscot County, was an imposing figure coming down the Aroostook River on the ice in his sleigh on February 12, 1839. Clouds of steam rose from the breath of his horse as it trotted along at a steady pace in the crisp cold air. At that time, most travel in the winter was done upon the frozen rivers, which were the highways of their day.

Hastings Strickland, Sheriff of Penobscot County.

Just prior to this, on January 23, 1839, the Legislature of Maine held a secret session at which they heard the report of George W. Buckmore, Deputy to Elijah Hamlin, then Land Agent for Maine. In December of

[1] Ketcum, Richard; John Diblee, John Bechell, R. P. Segee; and J. M. Connell, (Justices of the Peace in New Brunswick), Letter to Lieutenant Governor John Harvey of New Brunswick, dated Woodstock, February 15, 1839.

1838, Buckmore had traveled throughout northern Maine for ten days. He had come to determine the amount of timber being stolen and to arrest the timber thieves and break up their woods camps.

In his report to the Legislature, Buckmore reported that:

“…the amount of the depredations was much larger than had been anticipated. He was unable to arrest the trespassers or to take off their teams [horses] and supplies. He had found, a short distance above the Grand Falls, at Grand River from forty to fifty men at work making timber [cutting down the trees], and from twenty to thirty persons cutting timber on Green River…. Several crews were at work cutting timber on the Madawaska, St. Francis, and Restigouch Rivers. On the Fish River, he had found Mr. Whalen, with eight men and a team of six oxen, supplied by Francis Rice; C. Fernandee and S. [Simon] Hebert, with six men and one team; a crew of fourteen men and one team supplied by Mr. Carle of Madawaska; Joseph Dominkee, with nine men and a team supplied by Mr. Brunsieu of Canada [Quebec]; Mr. Woodbert and R. Martin, with fourteen men, one team of horses and one team of oxen; and several small crews, making about ten pair of horses, sixteen yoke of oxen and from fifty to seventy-five men. Most of these trespassers were located on Township No. 16, Range 7 [Eagle Lake] belonging to Maine.

On the main St. John River, between St. Francis and Madawaska Rivers, he found two crews under Leonard R. Coombs; one under Messrs. Wheelock and Carton, supplied by Sir John Caldwell; and one crew each under S. Hebert, William Gardner, Mr. Hunnewell, Messrs. Makay and Decenado, Mr. Canada, and D. Dagel, nine crews in all. They would probably cut on the St. John and its tributaries above the Grand Falls at least seventy-five thousand tons, one third of which would be cut on Fish River…

On the Aroostook River, on its tributary Beaver Brook, Buckmore found crews supplied by Peter Bull who informed Buckmore that since there was trespassing below [down the river], he would not stop and would resist any attempt to take away his teams. On Salmon Stream, another tributary, Wilder Stratton, James Swetor, David Sweter, Michael Keeley, John Coffee and John Smiley, all from New Brunswick, were at work, did not intent to quit, would defend themselves and resist all authority from Maine.

On Township Letter H. [part of Caribou today], Mr. Johnson, with a crew of ten men, six oxen and one pair of horses, refused to quit, would continue to cut timber in spite of both Governments [US and Canada], and used much threatening language. At the mouth of the Little Madawaska, there were about seventy-five trespassers with twenty yoke of oxen and ten pair of horses, well supplied with provisions from the Province [New Brunswick]. In Buckmore’s opinion they were violent and lawless men, determined to resist arrest. At the Aroostook Falls, he found thirty men with six yoke of oxen cutting timber within the American line and hauling it into the river below the Falls. Fifteen to twenty thousand tons of timber would be taken off the townships on the Little Madawaska River that winter…”[2]

[2] Tidd-Scott, Geraldine, Ties of Common Blood: A History of Maine’s Northeast Boundary Dispute with Great Britain, 1783-1842, Heritage Books, 1992, 127-128.

Based upon Buckmore’s report, the Maine Legislature sent the new Land Agent, Rufus McIntire, and his men to Aroostook with instructions to arrest the lumber thieves, confiscate their property, and stop the theft of the timber. This was the reason that Sheriff Hastings Strickland was coming down the ice on the Aroostook River that cold February day in 1839. Accompanying the Sheriff as he drove his sleigh down the river, were 200 men, all volunteers and part of the armed civil posse called the “Aroostook Expedition.”

Rufus McIntire, Land Agent for the State of Maine.

Rufus McIntire had gone on ahead of Sheriff Strickland and the posse to tell the settlers living along the Aroostook River why he had come and to reassure them that he planned to put a stop to the theft of timber. This turned out to be a bad idea because most of the settlers were from Canada and, unbeknownst to McIntire, nearly all of them were engaged in the theft of the timber themselves in one way or another. They alerted the other lumbermen and a group of them were ready and waiting about a mile up river from where the Aroostook Center Mall is located in Presque Isle today when the Sheriff’s sleigh came down the river from Masardis. Two days later, this location was called the “Theatre of Troubles,” by several New Brunswick Justices of the Peace.[3]

Coming down the river Sheriff Strickland came in sight of the group of fifteen or sixteen armed men who had formed a line across the river on the ice. There were other men with two teams of horses that were attempting to escape towards Canada to avoid being arrested and having their horse teams confiscated. The men lined up across the river intending to prevent the Sheriff from arresting the escaping men and taking their horses.[4]

[3] Ibid.

[4] McIntire, Rufus, Report of the Land Agent, 1840, 4-5.

Strickland was a large man, and definitely not someone to be messed with. He didn’t intend to let a group of armed lumbermen standing in a line across the river stop him from capturing the escaping timber thieves. He drove his horse and sleigh directly at the line of men standing on the ice and passed through the line in pursuit of the fleeing thieves as the men moved aside so they would not be run over by Strickland’s sleigh. As he drove through the line, some of the lumbermen who had been attempting to block the Sheriff from pursuing the thieves, shot at Strickland.

Fortunately, the men did not have good aim and rather than hitting the Sheriff, one of the bullets wounded the Sheriff’s horse, and other bullets damaged the Sheriff’s sleigh. The horse sustained a relatively minor injury and the Sheriff continued to chase the escaping men with his bleeding horse. He knew that the posse was coming along behind him on the ice and would deal with the 15 or 16 men who had shot at him and tried to prevent his pursuit of the thieves.[5]

Sheriff Strickland pursued the escaping thieves down the ice of the Aroostook River for six or seven miles before he was able to overtake them and arrest them. He brought the men back to where the other men who shot at him were being held by the posse.

[5] Ibid, 5.; and Hamlin, Elijah, Report of the Land Agent, 1841, 47.

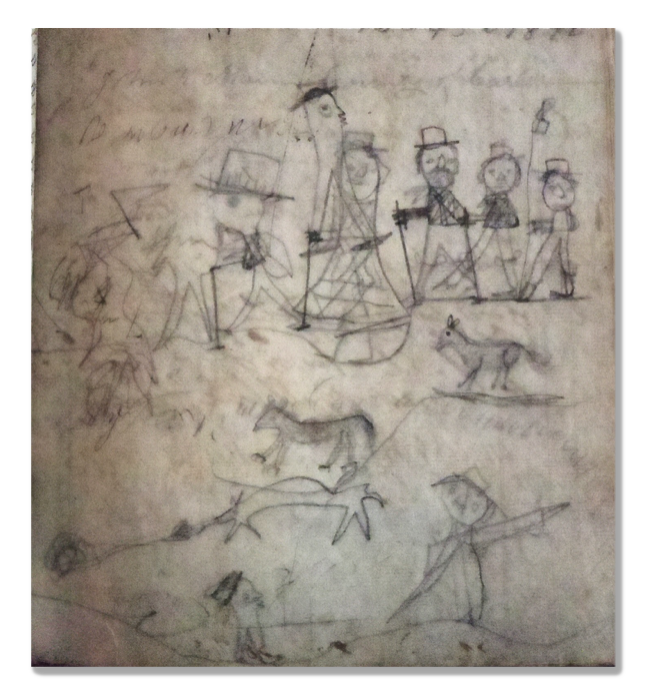

Pencil drawing from the Account Book of Jonas Fitzherbert of Perth-Andover, New Brunswick drawn at the time of these incidents. It probably depicts the chaos on the Aroostook River that February day in 1839.

In all, the Sheriff arrested between ten and sixteen men on the ice of the Aroostook River [6] in Maysville [the north half of present-day Presque Isle]. Ultimately at least five of the men were charged with timber theft and four of their teams of horses were confiscated. A Magistrate accompanied the posse allowing for their trials to be held right there on the ice of the Aroostook River. Of those arrested and found guilty, five were transported to jail in Bangor – which was the closest jail at the time, arriving there on February 18, 1839. [7]

Although no records exist today to tell us the names of all of the men who were arrested, we do know that Dennis Fairbanks, an early settler in Presque Isle, and Ebenezer Webster, who had come with the Land Agent’s party and was heavily involved in the lumber industry in the region, together posted bail for Peter Bull, the first settler in Maysville [now Presque Isle]. There were two others, Charles Johnson, another early settler along the Aroostook River, and Mr. Nary (or Hay [8]) of whom nothing more is known, who were ultimately released after being held for two hours. It is unknown today how long the five men remained in jail in Bangor.

Asa Dow, a prominent Canadian lumberman heavily involved in timber trespass in what is now Aroostook County, gave a sworn statement about the incidents on February 14, 1839 (two days after Sheriff Strickland arrested the men on the Aroostook River). Dow said the word that the posse was coming had reached the lumbermen before the posse arrived. The lumbermen had agreed with the settlers along the Aroostook River that they would cooperate with each other to oppose the posse and that they were willing to “do battle.” According to Dow, after the lumbermen and settlers originally had waited for a while and the posse didn’t arrive, they all went home. However, contrary to Dow’s testimony, it is clear that not all of them did go home. Some of them remained and ultimately shot at the Sheriff.

Asa Dow said that when the group waiting to ambush the posse upon their arrival dispersed (as we know not all of the group did), he went to Tibbetts’s, an inn and gathering place for locals which was located near what is today Perth-Andover in New Brunswick. He said that when he got there, he found many men gathered there who planned to “surprise the American force and capture their teams [horses] and men.” He said, “it was our intention to fire upon and shoot the teams” once they had them at the Tobique (as Perth-Andover are was then referred to due to the Tobique River in the vicinity). [9]

It is also known that these men at Tibbetts had broken into the storehouse of military arms located in Woodstock New Brunswick for the purpose or arming themselves. Major John Harvey, Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick issued a proclamation on February 13, 1839 (the day after the Sheriff was shot at). In the proclamation, he ordered all the people who broke into the weapons storehouse and stole the weapons to return them. [10] In a letter dated February 15, 1839, addressed to John Harvey, a group of Justices of the Peace told Harvey that “the arms which had been taken from the warehouses in this place [Woodstock] have all been restored to their respective places of deposit.” [11]

[6] Public Records Office, London, Correspondence of State Pertaining to New Brunswick from 1836-1838, and the 1839 January – March Dispatches, Provincial Archives, Fredericton, Transcribed by Dena Winslow. Transcription page 16.

[7] McIntire, 5.

[8] Public Records Office… transcription page 16.

[9] Public Records Office… transcription page 9-10.

[10] The Democrat, February 19, 1839.

[11] Ketchum et al.

In his Proclamation, John Harvey claimed that New Brunswick had been invaded by the posse (this was because he claimed that northern Maine north of Mars Hill Mountain belonged to New Brunswick – which it did not). He also ordered militia troops to be drafted and to be ready to fight, “should the occasion require.”[12]

Following the arrests on the ice near Presque Isle, the posse was directed by the Land Agent, Rufus McIntire to go to the mouth of the Little Madawaska near present day Caribou where it was believed that another group of trespassers were at work stealing timber. The posse traveled on the ice of the Aroostook River, however, they found that all of the timber thieves who had been working there had escaped to Canada before they arrived.

While the Sheriff and the posse went to present-day Caribou, the Land Agent, Rufus McIntire went on to present-day Fort Fairfield to an inn, run by James Fitzherbert (a Canadian – and brother to Jonas whose journal contained the drawings from the events of the Aroostook War). The inn was located about 2 miles on the US side from the present border crossing between the US and Canada at Perth-Andover and Fort Fairfield. McIntire had been told that there was a large gathering of the settlers living on the river being held at Fitzherbert’s but when he arrived he found no one gathered there. However, he had also requested a meeting with a Canadian official, James McLaughlan, to discuss the timber theft situation. That meeting was to be held the following day on February 13, 1839. McIntire, knowing he was miles from the Sheriff and Posse who had camped out on the ice of the Aroostook River near Presque Isle, decided to spend the night at Fitzherbert’s inn and travel to the Tobique the next day to meet McLaughlan. He did not expect any problems because he believed that all of the timber thieves had either been captured or had escaped to Canada.[13]

Asa Dow testified under oath in Fredericton that Penderson H. Beardsley (another prominent and well-known timber trespasser originally from Woodstock, New Brunswick, but who was living along the Aroostook River at the time of these incidents [14]

) returned to the Aroostook River from Tibbetts where the lumbermen were then gathered, taking several people with him whom he stationed at different places to keep a watch and see what the American posse was doing. Paul Beardsley joined him in keeping watch, and it was Paul whom Asa said had returned to Tibbetts to inform the group that five Americans were staying at Fitzherbert’s for the night. He reported that the rest of the posse was camped a few miles up the Aroostook River.

[11] Ketchum et al.

[12] Ibid.

[13] McIntire, 6.

[14] Public Records Office… transcript page 15.

Asa Dow said that once he found out that the Land Agent was at Fitzherbert’s he ordered two sleds of horses to be harnessed and took fifteen to eighteen men in the two sleds with him to Fitzherbert’s. Dow testified that all of the men were “armed with muskets and rifles and loaded with powder and ball. I think the bayonets were fixed [attached to the guns ready for use].” [15] At about midnight, Dow said he had some of the men surround the house and some went inside with him.

Asa Dow and his men (whom McIntire called a “lawless mob,” [16]

) captured McIntire, along with Mr. Gustavus Cushman, and Mr. Thomas Bartlett, who were members of the posse; and Mr. Ebenezer Webster [the same man who had earlier in the day posted part of the bail for Peter Bull], and Mr. Pillsbury, who had accompanied the Land Agent.

When the men at Fitzherbert’s were awakened and were getting dressed Asa Dow said he entered their rooms and told them they were under arrest. Ebenezer Webster was reported by Asa Dow to have asked by what authority they were being arrested. Paul Beardsley, who was also present, had a gun in his hand and he dropped the butt of the gun on the floor and said to Webster, “that is my authority!”

The five men who had been captured at Fitzherbert’s were transported on sleds to Woodstock by the lumbermen and turned over to Canadian authorities who put them under arrest and sent them to jail in Fredericton. [17]

McIntire feared for the safety of the posse. He wrote, “while at the hands of the mob and apprehending an attack on the posse, by the force [large number of men] I saw moving in that direction, the most uneasiness I felt, was, that I had been made the instrument of lulling the Sheriff into a false security and exposing him to surprise.” [18] He expected that the Sheriff and posse would be attacked by the armed men he saw heading towards where they were located on the Aroostook River, and he had no way to warn them.

Asa Dow testified that he had been lumbering on the Aroostook River and that he “had no authority at all to lumber there.” He added, “I consider myself a trespasser.” He also admitted that the people he had been involved with who planned to attack the posse and who had been hiding and watching the posse were also involved in timber trespass. [19]

Following the capture of McIntire and the others, Asa Dow also testified that about thirty-eight or forty men remained at Tibbetts who had all decided to go and “surprise” the posse, in other words, to attack the posse. He added that, “two or three Indians were taken to go and spy out where the American force encamped and to inform us, but they did not go.”[20]

Upon learning that the Land Agent had been captured, Sheriff Strickland ordered the posse to go back up the ice to Masardis and prepare for what they had been told was to be a planned attack by the Canadian lumbermen. The Posse retreated to Masardis where they put up a sort of barricade of logs, known as a “breastworks” to protect themselves, and prepared for a battle with the armed Canadian lumbermen.

[15] Public Records Office… transcript page 11.

[16] McIntire, 6.

[17] Public Records Office… transcription page 10.

[18] McIntire, 6.

[19] Public Records Office… transcript page 11.

[20] Public Records Office… transcript page 11.

Sheriff Strickland made a similar but far more heroic ride than Paul Revere had made more than 60 years earlier – although for similar reasons. Strickland rode nearly non-stop from Masardis[21] to Augusta on horseback – about 200 miles with 160 miles of the trip through the woods in the winter in the bitter cold – stopping only at settlers homes for fresh horses along the way. He made the 160 miles of the trip through the frozen February woods in record time, having left Masardis at 1:30 pm on Thursday, he arrived in Augusta about 50 hours later at 4:00 pm on Saturday. As W. T. Ashby described it, “the wild animals alone witnessed that rapid ride through the gloomy woods. Strickland was acting the part of telephone, telegraph, and locomotive… at 4:00 pm his steed’s feet were clattering up the Main street of Augusta…” [22] Unlike Revere, Strickland was not captured during his journey, and was able to alert the Maine authorities that the British were coming… much like Paul Revere had done in Massachusetts. [23]

A ballad of the day says:

Fast rushed the teams past Number ‘Leven, [Ashland]

And ere the clocks had pointed seven,

They halted at Masardis.

An unnamed woman living in Masardis at the time, and obviously a British supporter, wrote the following at the time of the events:

Come all ye noble Yankee boys, come listen to my story,

I’ll tell you about those Volunteers and all their pomp and glory.

They came to Aroostook their country to support,

They came to St. Croix [Masardis] and there they built a fort.

They started down the river some trespassers to find,

They came to Madawaska Stream, and there they formed a line,

But McIntire and Cushman they thought it too severe to lodge with private soldiers,

To tavern they did steer.

They came to one Fitzherbert’s at 8 o’clock at night

Where these poop weary officers expected much delight.

But instead of taking comfort, as I think you will see,

They were taken by an Irish mob and hauled to Fredericton.

Then on parole of honor those gentlemen went home,

And never to Aroostook were they again to come.

When Rhines and Strickland heard the news they knew not what to do,

Their heads were quite distracted, and their hearts were full of woe.

Strickland turned unto his men and to them he did say,

We’ll retreat back to Masardis – we can do it in a day.

They came to Col. Goss’s [Masardis], they halted on the shore,

Such a poor distressed company you never saw before.

Some with empty stomachs and some with frozen feet,

This is a father in Rhines cap, this seventy mile retreat.

Now they’ve gone across the river, a breastwork for to build,

For fear the British would come up and they would have to yield.

‘Tis built of spruce and many cedar tree,

So neatly framed together is this famous battery.

And now we defy the British Queen and all her red coat crew,

To beat our noble Yankee boys, let them try what they can do. [24]

[21] McIntire, 6.

[22] Ashby, W. T., “A Complete History of Aroostook County and it’s Early and Late Setters,” Mars Hill View, December 23, 1909 – Oct. 6, 1910.

[23] Bangor Whig, Friday, February 15, 1839.

[24] Winslow York, Dena, The History of the Greater Ashland, Maine Area, St. John Valley Publishing Company, 1983, 33-34.

On February 13, 1839, Lieutenant Governor John Harvey, of New Brunswick, sent a letter to Governor Fairfield in Maine demanding that he remove the posse from the area and threatening if he did not remove them, then he would use military force to remove them. To Maine authorities, this was a threat and a blatant attempt to take control of the land that Maine owned. By February 15, 1839, Harvey had begun to carry out his threat and began deploying British troops to the region.

A few days later, on February 16, 1839, James McLauchlan, the Land Agent for New Brunswick, and Benjamin Tibbets, a prominent lumbermen, owner of the inn near Perth-Andover, and an apparent leader of the group of lumbermen, went to Masardis to talk with the Maine Posse who were there. McLauchlan and Tibbetts planned to demand that the posse leave. They were promptly arrested by the posse and sent to Bangor to jail.[25]

On February 18, 1839, Major General Isaac Hodsdon was ordered by the Maine Legislature to muster a force of 1,000 militia and proceed to Aroostook to assist the Land Agent and his posse. In addition, the State ordered a draft of 10,343 militia to be ready to be called out for active service if needed. In total, 2,904 militia were actually marched to Aroostook. In addition, Federal Troops were stationed in Houlton at Hancock Barracks with a force of 120 artillery men. However, they were told by the Federal Government to remain neutral unless directed to become involved in the Aroostook War – which they ultimately did not.

When Maine’s Militia arrived in Aroostook a few days later, W. T. Ashby’s mother, age sixteen years old at the time was watching the procession come down the Aroostook River on the ice in Maysville [now Presque Isle]. Ashby described what she told him about it:

[25] The Democrat, February 18, 1839, Transcription by Dena L. Winslow, page 45.

“While the church bells were ringing in Augusta the Sunday morning after Sheriff Strickland’s arrival, 50 armed men left the city for the Aroostook river. Early the next morning the roll of drums and the shrill notes of the bugle echoed from one town to another….within a week, 10,000 troops were in Aroostook or on their way there…

The first regiment soon reached No. 10 [Masardis], and at once proceeded down river on the ice. If the startled and frightened settlers were startled and frightened when the Sheriff’s posse came, they were dumbfounded and paralyzed now. As the sun settled toward the treetops one beautiful, winter evening, the sound of music was heard. Nothing like it had ever been heard in that country before. Children playing out of doors ran to the house and hid or clung to their mothers; the cats ran up convenient trees, and dogs bristled up and howled; it was a strange, wild, weird sound. It was a military band coming down the river.

Soon the procession came in sight – and what a sight – long rows of men, all dressed alike walking in straight lines and keeping step to the music; officers on horseback rode on either side, and one tall man carried a beautiful silk flag trimmed with gold lace rosettes. It was the ‘Star Spangled Banner,’ and many of the little crowd gathered at the Johnson Landing [on the east side of Maysville – now Presque Isle - on the Aroostook River] had never before looked at the flag of the free.

Behind the soldiers came long rows of double teams loaded with men and supplies. The regiment halted; a double sled was driven up close and the awe stricken settlers gathered nearby saw the men unload a long, shiny, yellow looking thing mounted on wheels that looked like a peeled hollow log. It appeared to be very heavy, and it was; it was a brass field piece [cannon] loaded and ready to use.

An officer waved his sword; the men stepped back into line and a man with white pants stepped forward and pulled a string. A stream of fire and smoke rolled down the river, and the first cannon shot in the Aroostook Valley boomed and echoed from hill to hill. It was heard by the settlers on Fitzherbert Brook [now Fort Fairfield] six miles away, and by the regiment of Maine Militia near Portage Lake, in route for the present site of Fort Kent….” [26]

[26] Ashby.

Aroostook War Cannon located in front of the library across from the blockhouse in Fort Fairfield.

John Harvey in New Brunswick continued his military build-up and ordered up a draft of about 950 men who were called into actual service, with an additional 1,398 British Regulars standing by to assist if needed. Both sides began to build roads, bridges, blockhouses and barracks for the troops as they prepared for the impending war. Maine’s Governor Fairfield responded to John Harvey’s February 13 letter by saying that Maine would meet any use of military force with similar force. By March 3, 1839, the US Congress passed a bill authorizing the President to call out 50,000 militia to support Maine if needed. Surrounding New England states passed resolves to assist Maine as well should a “collision” occur.

Many of the roads in use today were constructed during the Aroostook War period (the State Road in Presque Isle leading to Ashland is one example), and there are a few buildings remaining that were built during the War. In addition, two blockhouses remain today: Fort Fairfield, which is a reproduction built from the original plans; and Fort Kent which is the original structure. There were barracks, roads and bridges built in New Brunswick as well, and as far away as Quebec – all preparations were made for the Aroostook War. In addition to the two remaining structures, for which the towns they are located in are named, there were also structures built for the War in Presque Isle, Ashland, Masardis, Soldier Pond, and Bridgewater – however, little to nothing remains of those structures today.

There was a great deal of activity for the troops at the beginning of the war. In addition, there were a number of skirmishes with lumbermen and arrests were made. At that time, logs were floated to market in the rivers and streams each spring. This was big business and fortunes were made from the stolen timber at that time. In Fort Kent and in Fort Fairfield, the blockhouses were used to protect log booms across the rivers that kept any logs from going down the Aroostook and St. John Rivers and into Canada.

By March 21, 1839, Winfield Scott had come to the area representing the US and was able to reach an agreement with Lieutenant Governor John Harvey to prevent further battles from occurring. The Aroostook War came to an end with very few casualties and few actual battles fought, thus it became nicknamed “The Bloodless Aroostook War.” This does not mean that people didn’t die during the time period, because they did. In fact, an unnamed Militia member died at a home in Maysville [now Presque Isle], located on the bank of the Aroostook River just west of the present location of where the bridge crosses the river toward Caribou. Although Commander Hodsdon’s records do not indicate who the man was, or exactly what he died of, [28] there are several other records at the State Archives in Augusta indicating that soldiers died of various illnesses (with 2 soldiers graves located at Soldier Pond), and there were some serious disabling injuries that occurred as well.[28]

And, of course, there is the famous Hiram Smith, whose gravestone is to be found in the Haynesville Woods south of Houlton. Hiram was a Federal Private coming to be stationed in Houlton. There are no records existing today that tell us what Hiram died of, but he did die and was buried along the road somewhere in the general vicinity of where the grave stone is now located. This stone was added a lot of years later, when no one knew for sure the location of his actual grave. The first stone erected was subsequently stolen – as was a second one. The present stone says Hiram Smith died in the “Indian Wars” – although it is unclear why it would say that. The famous Dick Curless song, “A Tombstone Every Mile” is based in part on Hiram Smith’s grave stone in the Haynesville Woods. Other songs and stories have also been told about Hiram and his too-early demise.

[27] Hodsdon, Isaac, Letters, records and papers from the period he commanded the troops during the Aroostook war, privately held collection.

[28] Maine State Archives, Aroostook War Vouchers; and Resolves of the Maine State Legislature.

The current grave stone for Hiram Smith in the Haynesville Woods.

There is also a lingering legend about a cow being shot in the field when the soldiers were celebrating the end of the war at Fort Fairfield. However, there is some evidence that it was a local farmer working in his field who was accidentally shot and killed by the celebrating troops. Records existing today do not tell us for sure which it was – or even if this actually happened.

Attack on Fort Fairfield

After the first conflicts ended, a limited number of troops remained to continue to keep the peace and oversee the prevention of continued theft of Maine timber. In the fall, on September 8, 1839, a group of lumbermen gathered at Benjamin Tibbetts store in the Perth-Andover area. They were not happy that the troops remained at Fort Fairfield because they were preventing the men from taking supplies into the woods in Aroostook County to steal more timber. By dark of night, the men proceeded to Fort Fairfield to attack the Fort. However, a sentry spotted them and fired a warning shot over their heads. The men were so frightened by the warning shot that they ran away so fast tripping and falling in the darkness as they went, that they dropped some of their weapons and some even lost their boots as they scrambled to get away. The sentry recognized the men and they were later reprimanded for their actions.

Aroostook War soldier from the Account Book of Jonas Fitzherbert drawn at the time of the Aroostook War.

A great deal of timber was still being floated down the rivers and into the sawmills of New Brunswick in Fredericton and St. John. However, much of it was now being done through permits – and some of the timber thieves were allowed to pay a penalty and keep the trees they had cut so that they could float them down the rivers to market in New Brunswick. In 1947, Thomas LeDuc nicknamed the Aroostook War, “The Pork and Beans War.” However, this does not fit for two reasons… the first is that ultimately, the Aroostook War was about who owned northern Maine. The British especially wanted to take possession of part of what became Aroostook County so that they could own the land, then owned by Maine, that included their “Communication Route” or road system along the north side of the St. John river. This was the major “cause” of the Aroostook War. Ownership of the land, and the resources on the land (including the timber resources) was the primary reason for the Aroostook War, and timber theft by Canadian lumbermen was only a secondary reason.

In addition, at the time of the Aroostook War, lumbermen did in fact eat a lot of pork as the many records in the State and Provincial Archives document. But, they ate very few beans while working in the woods at that time. There is only a record of one small bag of beans being taken into the lumber woods during this period. It was much later, in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s that beans became regular fare in the lumber camps. Thus, calling the Aroostook War the “Pork and Beans War” would be like calling it the “Chainsaw War.” Chainsaws didn’t exist yet, - and lumbermen didn’t eat many beans in the woods camps during the Aroostook War period.

The Aroostook War was about the ownership of the land and the resources on that land. The use of an inaccurate and inappropriate nickname also attempts to lessen the importance of the Aroostook War – which is the only time in US History that a State has declared war on another country; and the importance of a potential third major conflict between the US and England – which was narrowly averted with both sides having troops in place ready to do battle. As mentioned earlier, a limited number of troops remained after the end of the war – on both sides of the border. They were ready to go to battle at any moment if needed. However, relations between the troops on both sides of the border became reasonably friendly over time. For example, the commander of the troops in Fort Fairfield regularly held sharp shooting competitions between his troops and those in Perth-Andover on the Canadian side. He provided a silver pocket watch as the prize for the contests. The soldiers in Woodstock regularly came to Houlton and although the rare skirmish did break out over someone thinking that a US militiamen had insulted the Queen of England, for the most part, relations between the forces were congenial.

The Aroostook War had a huge positive impact on the region. Settlers were able to earn an income by selling food and produce to the troops, and by lodging and feeding troops. They supplied horses and cattle, and feed for the animals as well. In addition, militia members were offered free land in Aroostook County for their services after the war and many did come with their families – and their descendants remain in Aroostook County today. A lot of road building and settlements were developed, and some of the bigger towns developed.

While the troops were building Aroostook County and nearby New Brunswick and Quebec, State and Federal negotiators continued to work with the British officials in New Brunswick and England to resolve the matter of the location of the border and ownership of the land. Ultimately, Daniel Webster, the Secretary of State for the US and Lord Ashburton, representing the British, were able to reach a resolution and the Webster-Ashburton Treaty was completed on August 9, 1842 (and ratified by Great Britain in 1843) which established the border where it is located today.

Although the British were not successful in taking all of northern Maine – down to Mars Hill as they had attempted to do, they did succeed in gaining 5,500 square miles (about the size of the state of Connecticut) that did not originally belong to them based upon the Treaty of Paris that established the border near the St. Lawrence River in 1783. The British were also successful in keeping control of the communication route – which was so all-important to them. Maine did ultimately receive compensation from the US Government for the lost lands, in the amount of $150,000, [29] and greatly benefitted from the development and settlement of the region that occurred as a result of the Aroostook War and the Northeast border controversy.

[29] Ashby, W. T.